i'm still mulling it over.

this evening i heard

gary drescher speak about whether or not there is a place for ethics in a mechanical, deterministic universe. ultimately, his conclusion is that there is, and while i wasn't fully on board with his argument as to why, i do agree, and i'm willing to cut him some slack. after all, it isn't the easiest case to make. i'll talk some about how he presented his theory, but i ask you to forgive me if i don't do a bang-up job

of it. i, after all, am not a philosopher, just a girl with enough time to kill to spend three hours on a tuesday night deciding she isn't fully on board with a philosopher, and am not trained in the proper case-making techniques. but this is my house and i'll stand on a chair in the middle of it and talk to myself if i want to, and you, as always, are welcome to stand on a chair next to me, or sit in a different room, or kick the front door down and flee, or watch secretly through the window. i ask only that you don't sneak up behind me and knock me off of the chair, because if i'm in a coma no one will feed the cat, and she doesn't deserve to suffer for my, or your, actions.

first, the nature of the deterministic universe.

it's pretty simple, really:

each of those horizontal planes represents a finite instant in time, like a polaroid of the entire universe. if you accept that the universe is governed by laws of physics that apply with equal weight to everything within it, then you can take any one of those snapshots and calculate all of the future (and, theoretically, past; you may as well buy it, this is all conjecture anyway) actions and positions of everything in the image. so, if you can do the math, and all of spacetime is governed by the math, then once you have any one slice of spacetime, the entirety of it off into infinity in either direction is already carved in stone. that means that all of your actions are written, too. it's as if the day you were born you were handed a gigantic flip book with a stick-figure you reading a flip book of its own drawn on every page, and the time it takes you to turn a page is the time that elapses from each page to the next. you don't know when you're looking at page 29,457 that on page 18,946,273,125 you'll be eating a pluot and scratching your left eyebrow, but the drawing is already finished. that sort of thing.

second, i am not about to argue that anything anywhere is predetermined. sometimes i wish i could, as you'll see in a minute, but it isn't a theory i've ever been able to embrace. i'm working within the boundaries of that theory this evening because the discussion hinges on that supposition, but it's just a discussion. please do not send me your dissertation on why everything is random; i love quantum theory as much as you do, i'm just having a little chat. of course, don't send me your dissertation on why nothing is random, either. my stance is this: no one can prove anything beyond my reasonable doubt. and i'm o.k. with that. i'm great with that. i have no desire to be any more certain of anything of that nature than i am right now. i am going to make whatever choices i am going to make, either because i can't help it or because i have helped it, and that is a beautiful, beautiful truth.

the thing i take issue with is the common desire to apply the terms "futile" and "meaningless" to the choice-making process when one is assuming that the outcome of a choice is extant prior to an individual's realization of which choice it is that he or she is making. people love to argue that in this case the individual isn't making a choice, but of course that isn't so. "making a choice," as drescher explained, is a mechanical process, like walking. when you walk from point a to point b with the aim of getting to point b, you have engaged in a process similar to making an intellectual decision based on your desire for a specific outcome. to say you aren't making a choice because the outcome of the process is predetermined is like saying that when you walk in a direction that leads you from point a to point b and could have led you to no other point, you didn't actually do any walking. you know you did. you

know you did.

i assume what people mean by "futile," in this instance, is that the decision has no impact on the outcome of the decision maker's own life, and i wouldn't disagree with that in this context (we are remembering, bunnies, are we not, that i do

not believe that is the kind of world we live in?). but that doesn't make it futile.

remember that flip book? let's change it around a little. imagine the pages spreading out into an arch, arranged in a profoundly meticulous order that allowed the arch to maintain its shape with no outside supports, like one of

these:

now, of course the metaphor doesn't carry completely, as all of the slices of spacetime are equal in proportion*, and in order to make an arch functional you need to vary the sizes of the stones. too, this arch was built by a british middle-school student, and the spacetime continuum is, well, the spacetime continuum, but that means it isn't a flip book, so if you were down with that image you may as well accept this one. the flip book is now an arch, and if you remove any one page the entire structure collapses. when the structure is the universe, the outcome of something like that is, you know, bad. quite bad.

so remember now that on every page in that flip book that you occupy, you are engaging in an action, an action that is the result of a choice that you made (yes you DID, we just went through that), and even if that choice-making process was irrelevant to the ultimate outcome of your own personal life, it was hugely important to the big picture. the process led to an action that occupies a position in spacetime, and if there were suddenly nothing where now there is you engaging in that predetermined, necessary action, the entire arch would fall down on top of itself. it may be true that you can't control, or even affect, the workings of the predetermined universe, but you are still contributing to them, just by being here or there or wherever you are, because that is the place you had to be in to keep the whole unknowable thing from disintegrating or imploding or doing whatever it is a spacetime continuum does when it gets all fucked up. that is a massive responsibility, one that, if you don't believe in determinism, could crush you, paralyze you. i mean, how many of you have lost fifteen minutes in the cereal aisle, frozen before the array of whole grains and sugar-coated puffs and flakes with berries and oat clusters with nuts? we labor over decisions like that, truly, honestly struggle, even though it's just cereal and if you don't like it you don't have to eat it, and all that's gone wrong is you have three fewer dollars than you had yesterday. your kitchen and the supermarket will not cease to exist if you decide there aren't enough berries in the flakes—unless they will. no, they won't, but do you see how much easier not having to wonder whether this or that decision is The Decision makes everything? if you don't like the flakes, well, there's nothing you can do about that, you just aren't going to like the flakes, because spacetime doesn't want you to like the flakes, and something you move on a shelf when you go back to the supermarket tomorrow to buy the oat clusters you think you should have bought in the first place (but, of course, shouldn't have) will shift just the right number of atoms to keep the entire universe right-side up. it's so easy. it's genius. and yet people whine about the very notion of it, because they think it robs them of purpose. universe, right-side up, thing you moved. how much more responsibility are you after?

it's narcissism, then. when people say "futile," they mean on a personal level, but if you believe in a deterministic universe, which is by definition a universe where all matter is connected, since determinism only works if particles interact according to static physical laws, then there is no such thing as a personal level. there is only one level, on which all matter is even and impacted equally by every action in every immeasurably small fraction of time. people say "futile" because they don't know how to imagine all of that without themselves at the center. but we're nowhere near the center. seriously. not even close. of course, if you believe in a deterministic universe, then you are forced to accept that all of those narcissistic people were programmed to be precisely that way, and that's a tough one. well, for me it is, because i want to shake them out of it. but then, wouldn't that mean i was predestined to want that? i am saving the universe right this minute, simply by telling all of you navel-gazing monkeys to get right the hell over yourselves.

this gobbledygook circles around on itself infinitely, especially when i'm spewing it from atop a chair in the middle of my house, so i'm going to move on to the next point of interest.

you may remember that the point of drescher's discussion was to support the idea that ethics are valid in a predetermined reality. of course, you may just as easily have forgotten, and at this point i wouldn't fault you for that at all. but now that i've reminded you, let's talk about that idea a little.

like i said, i agree. i believe that ethics have a role in every reality, and, like drescher, i don't think that morality is relative from situation to situation or culture to culture. but i don't agree with his reasoning for why ethical behavior is good or correct behavior. in his argument he employed the

prisoner's dilemma, a classic example of non-zero-sum game theory that i don't really want to let myself get started on right now. i'm going to skip straight to the

lesson of the example, which is that rationally it is in one's best interest to choose cooperation or actions that lead to mutual benefit, and because it is the rational choice for you, you should assume that others will recognize it is the rational choice for them, and when you and they all make that choice every time a dilemma arises, everyone will benefit all of the time. and that, drescher says, is the miracle of altruism—that it is, in fact, not altruism at all, but a kind of selfishness that you will inevitably be able to pass off as altruism under almost all circumstances, and that's just as good.

no, it's not. but (sigh, oh sigh, oh forlorn and heavy sigh) i'll take it.

altruism, i think, is a sort of platonic ideal that doesn't actually exist in this realm. even if you choose to engage in an act that you are certain you will suffer from because you know someone else will benefit, you still gain the comfort of knowing you did what you believed was the right thing, and that can be a greater reward than any physical or material gain. no person or animal does anything that they don't benefit from at all; that would be counterintuitive in terms of survival instinct and propagation of the species. but consciously choosing, for mathematically supported reasons, the action that you stand to personally benefit from the most is about as far from the idea of altruism as you can get. in the prisoner's dilemma, the altruistic decision is still to cooperate, but the decision would be made with the knowledge, maybe even the assumption, that you might wind up spending the rest of your life in jail for it. the decision to cooperate is only altruistic in this instance if you are making it solely for reasons of minimizing the other prisoner's sentence, and, as that is explicitly not the purpose of the game, the example says nothing about altruism. it does, however, make a beautiful argument for mutualism, and in this world where genuine selflessness can not exist, mutualism is about as good as it gets, and, honestly, far better than we've ever managed. i don't think, though, that this makes a very compelling argument for objective ethics, at least not as i understand them. too, you have to consider that the prisoner's dilemma was designed to prove a point about non-zero-sum scenarios, and it does this, but if it was built around the problem rather than being derived after observations of reactions to such a problem, it may not be entirely reliable. it also hinges on the assumption that all individuals involved in the problem are equally rational and likely to think the whole thing through in such a calm and calculated manner, which one can assume will rarely be the case. but, like i said, i don't know all that much about these things.

the discussion ended with some questions addressed to drescher on whether he thought this sort of "ethical" choice making was carried out by other species. now, i heard this question and made a little face, because i thought it was an insanely silly thing to ask, but when drescher said yes, he thought it carried through most species, a lot of people seemed taken aback. the moderator actually closed the discussion after saying that the idea that evolution might have wired animals to be oriented toward mutual benefit kind of blew his mind. it was good that he wound things up then, because i was getting ready to make a not-so-little face and maybe stand on a chair in the arts section of mcintyre and moore instead of waiting until i got home. even the most cursory examination of any animal population from now back through to the dawn of multicellular organisms would prove immediately that this is the only kind of decision being made by every species—except humans. what we started out doing exclusively, by instinct alone, is now a jaw-dropping concept that a circle of apparently intelligent people who have gathered to talk about that very concept can just barely get their minds around. ants and bees live in colonies and work only for the good of the colony, because the good of the colony is the good of the insect. americans now regard ants as the absolute worst pest they can have in their home. they've beaten the cockroach, ladies and gentlemen. i can't wait to see what

catherine chalmers does with this one.

and that, my sweetnesses, my everythings, is why i can't believe in a mechanical, deterministic universe. how could something that started out so well have devolved to this point where we have to plan meetings to debate whether or not it's in our best interests to look out for each other? how could that be a thing that's meant to happen, that has to happen? granted, i can't make guesses about the page in the flip book 14 billion pages from here, and anything, i mean

anything, could be going on down there, but if the universe is arranged in a way that serves its own needs in the most ideal manner possible . . .

gah. i could make another speech, but my legs are tired, and this chair wasn't all that sturdy to begin with. maybe the earth is a thing the universe hates, like a giant whitehead on its pre-prom forehead, and we're the bacteria inside, and for the past 4.6 billion years it's been all the universe could do to not squeeze us out all over the mirror. don't be snickering over there in your smarty-pants wire-rim glasses, my guess is as good as yours and you know it. at the end of the day, we convince ourselves of whatever it is that lets us sleep, right?

i say we always have the opportunity to make the right choice. and then i say good night.

* they're equal in this newtonian model. more commonly, though, the idea that a moving object traces a line diagonal to the time axis as it moves through space leads to a conical diagram, like

this:

this makes the arch concept a little more plausible, since the diagram widens in both directions as you move away from the starting point, i.e., your present in which you are attempting to make a decision or engage in an action. but it's still, just, you know, whatever. it's the meaning of the thing that you need to understand, not the shape of the thing.

Labels: bug love, meaning of life, morality

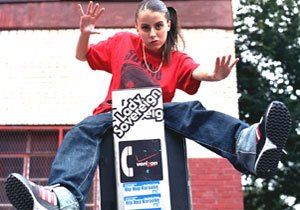

and that since she hit, trendy girls have been notably less likely to flare their trendy nostrils at my oversized men's kikwears and breakdowns. i don't know how anyone could look askance at the giant skater pants. they've got everything--they're more comfortable than pajamas, their roominess prevents their knees from ever giving way, and the back pocket that reaches all the way down the thigh is the perfect size for a folded copy of the new yorker. i recognize that this is not the intended purpose of the pocket; it was, i believe, originally intended to hold my gat, and was later co-opted so it could hold my white crowns and glow sticks. but i'm a grown-up now, so new yorker it is. maybe if more of those trendy girls held literacy in a slightly higher regard, they'd have a greater appreciation for the utilitarian beauty of the garment.

and that since she hit, trendy girls have been notably less likely to flare their trendy nostrils at my oversized men's kikwears and breakdowns. i don't know how anyone could look askance at the giant skater pants. they've got everything--they're more comfortable than pajamas, their roominess prevents their knees from ever giving way, and the back pocket that reaches all the way down the thigh is the perfect size for a folded copy of the new yorker. i recognize that this is not the intended purpose of the pocket; it was, i believe, originally intended to hold my gat, and was later co-opted so it could hold my white crowns and glow sticks. but i'm a grown-up now, so new yorker it is. maybe if more of those trendy girls held literacy in a slightly higher regard, they'd have a greater appreciation for the utilitarian beauty of the garment.