tu deviens responsable pour toujours de ce que tu as apprivoisé

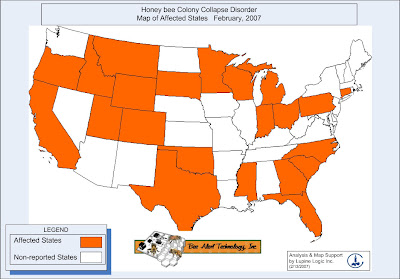

i'm sure that by now you've heard about the mysterious and massive drop in the honeybee population that has occurred over the last six or so months. the source is an undefined ailment being referred to, in the gently sterile and simplistic manner in which so many conditions are now discussed, as "colony collapse disorder." the problem was first reported on by bee experts at penn state, who were notified last november by dave hackenberg, a pennsylvania-based beekeeper who lost close to two-thirds of his bee colonies in about three months for no readily discernible reason. along with deaths and disappearances, the "disorder" appears to cause behavioral changes in the bees that amount to a sort of dementia--the bees don't care for their young or tend to the hive the way they typically would, they seem reluctant to eat their own honey stores or offered food, and queens have been seen ambling around outside their hives. while similar events have occurred in a more limited fashion in american bee populations in the past, ccd has reached pandemic proportions in past months and is leaving workers in both the apicultural and agricultural industries chewing their lips and furrowing their brows. professionally maintained honeybee colonies are responsible for close to a third of commercial plant pollination, and decreases in the population as significant as those being reported across the country right now could have serious impacts on produce yields, which could potentially shake up the economy in a big way. bugs matter, apparently. i can't help but think i've heard someone say that before . . .

in an ironic, unfortunate, and perhaps poetic-justice-infused turn, there's a chance that the industry may have, at least in part, brought this upon itself. postmortem examinations of afflicted bees have revealed signs of severely weakened immune systems, including high rates of fungal and bacterial infections. some showed evidence of the honeybee equivalent of kidney disease, with tubule inflammation and pyloric scarring apparent in up to 45 percent of the samples studied. the digestive tracts of dead bees contained pollen grains that seemed intact or undigested, an entirely abnormal finding. one theory is that immunosuppression could have been brought on by stress caused by things like frequent hive relocation (many beekeepers are migrant and move bees from location to location depending on which crops are currently flowering and/or in need of pollination) or hive splitting, an intrusive but fairly routine procedure in which ill or weakened colonies are physically merged with healthier colonies or given a new queen. hive splitting can also increase the rate of infestation or disease spread; if the beekeepers don't recognize the symptoms before they attempt to replenish the hive, they could be infecting an otherwise healthy colony and then moving it across state lines. in some cases, drought, hive overcrowding, or forced pollination of crops with minimal nutritional value for the bees led to diminished bee health, which would have left them more vulnerable to microbial or parasitic infestation. by treating their charges as a commodity rather than as living creatures with health requirements, even the most knowledgeable and seasoned beekeepers may be inducing their own losses. in the past these losses have been manageable and generally compensated for, but everything catches up with everyone eventually.

another theory, widely posited but difficult to prove, is that pesticides and insecticides used in commercial agriculture are responsible for the die-outs. the ccd working group has zeroed in specifically on neonicotinoids, a relatively new class of pesticides that the epa has classified as highly toxic to honeybees in cases of acute exposure. in combination with certain fungicides, the toxicity of neonicotinoids displays a thousand-fold increase. both neonicotinoids and the fungicides in question are widely used, particularly in corn and sunflower production. imidacloprid, a chemical in the neonicotinide family whose use in agriculture has recently increased, has also been shown to impair the memory and brain metabolism of bees, which would explain ccd-stricken bees' reported tendency to disappear from the hive or behave in a generally addled manner. unfortunately, there is little documentation of the pesticide's long-term or cumulative effect on bees, and it can be almost impossible to verify an entire colony's pollen sources. investigations into the levels and types of pesticide residues in affected hives are ongoing, but the lack of official proof to date hasn't led most researchers to cross it off their list of likely causes. the mites, viruses, and fungi affecting honeybees now have been common for decades and have never led to colony deaths on the current scale; something has to have changed.

i am, as you could probably have guessed, deeply saddened and more than a little frightened by the bee plague. i'm also terribly disappointed, as a lack of human foresight on at least one front is probably at its root. what has to happen before we learn to explore an action's consequences beyond its immediate impact on our finances? why would any farm that depended on honeybees to pollinate its crops use a pesticide that was proven to be dangerous to honeybees? a single night of frost in california makes network news broadcasts everywhere, leading every fruit-consuming individual in the continental united states to groan and whine for days about how much more they'll have to pay for orange juice, but a 50 percent reduction in an essential link of the food chain responsible for $14 billion worth of crop production warrants zero public discussion? nobody thinks they'll miss the bees, i guess, but we are, on the whole, not very smart about deciding what we do and don't want.

well, i love you, bees. i love you and i'm rooting for you, and i hope that all of you who have wandered away from your hives have banded together and formed a brave new colony in some bee shangri-la that no human can reach or pollute, and if you must remain there giggling and buzzing while we all kick ourselves for not treating you right while we had the chance, i won't hold it against you. if, on the other hand, you are in need of a place to hang your hats, you are always welcome in my mother's compost bin, no matter how many rude things my father mutters at you on his way past. ignore him. he doesn't understand.

Labels: antihuman, bug love, environment

6 Comments:

At 1:28 AM, Mikey B. said…

Mikey B. said…

Could it have anything to do with that really cold spell we had this winter? I know the temperatures dipped pretty low here in Pa and insects don't really care much for the colder weather.

Just some speculation on my part.

At 12:36 PM, juniper pearl said…

juniper pearl said…

beekeepers started reporting big losses in november, and i don't think the cold spell would explain the similar losses in texas and the southeast. besides, bees find ways of surviving cold weather, or there wouldn't be any bees, right?

At 2:11 PM, asdflkjhasdflkjhasdfkjh said…

asdflkjhasdflkjhasdfkjh said…

wow, I hadn't even heard of this until now. thanks for bringing it to my attention

At 4:41 PM, Mikey B. said…

Mikey B. said…

Contrary to popular belief, it does get cold in Texas. The northern panhandle gets more snow than I get here in Pa. It even snowed in Florida and Los Vegas this year.

Seeing as this all started in November, I guess that rules the cold out. We were exceptionally warm during that period.

At 10:08 PM, juniper pearl said…

juniper pearl said…

snowfall isn't necessarily indicative of temperature. it means it's cold enough to snow, but not that it's colder overall. it's doubtful that temperatures were at the root of it, because similar findings were reported in states with drastically dissimilar weather patterns.

At 9:43 PM, Dina R. D'Alessandro said…

Dina R. D'Alessandro said…

I used to have a pet bee when I was little. His name was George. He used to hide under the the eaves of our house and he'd hang out with me every summer for as long as I can remember. I wonder whatever happened to him...

Post a Comment

<< Home